The Six Honest Serving Men of Cyber Threat Intelligence

- Mayan Stegmann

- Feb 20, 2024

- 8 min read

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) has quickly become a popular, yet grossly misunderstood function within modern business. CTI sits in an awkward grey area between cyber security and intelligence tradecraft. It is a function that is often underestimated, and underutilised.

In this article I'd like to dive deeper into how the "5 W's and an H" checklist can be used in CTI practices to aid in the attribution of cyber activity.

The title is derived from Rudyard Kipling's poem, "I Keep Six Honest Serving Men".

"I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who."

The 5 W's and an H

According to Inoslav Bešker, the "5 W's and an H" (also referred to as the "5 W's", or the "5 W's of journalism") are rooted in the seven questions used in ancient Greece to communicate stories clearly. Aristotle coined these questions the source of the elements of circumstance or Septem Circumstantiae. The purpose of the questions were to distinguish voluntary and involuntary action. These elements of circumstances are used by Aristotle as a framework to describe and evaluate moral action in terms of What was or should be done, Who did it, How it was done, Where it happened, and most importantly for what reason (Why).

In modern times, journalism students are still taught that these are the fundamental six questions of newswriting. Reporters also use the “5 W’s” to guide research and interviews and to raise important ethical questions, such as “How do you know that?”.

How do these questions apply to threat intelligence? All intelligence seeks to answer questions, or as Richards J. Heuer put it, "Intelligence seeks to illuminate the unknown." When it comes to CTI, those questions are focused on cyber threats and threat actors. However, the two questions most overlooked in CTI practice are the "Who" and the "Why". CTI consumers (be they the SOC, security management, or the C-suite) primarily care about "what happened", "how it happened", "when it happened", and "where it happened". Don't get me wrong, these are critical questions to answer when dealing with cyber threats or potential security incidents, but this leaves a large gap in the investigation.

What Doth a Threat Actor Make?

The anatomy of a threat actor (TA) can be summarised by their motivation, capability, and intent. These are the driving forces behind threat actors. The most common adversaries we'd encounter in the field are state-sponsored groups, cyber criminals, and hacktivists, or as Stewart Bertram dubbed them, "The Unholy Trinity".

There are very clear distinctions in the modus operandi (MO) of these TAs, what drives them, and what their end goal is. A state-sponsored group will predominantly be motivated by political and strategic goals, and would present more advanced TTPs and cyber arsenals. Cyber criminals are motivated by financial gain; their MO and TTPs may vary based on the TA, but would generally follow the same principles. Hacktivists on the other hand are seldom motivated by monetary gains. They are driven by ideology and seek justice for their causes. They may not have the same level of funding and capability as a state-sponsored actor or cyber criminal group.

These lines, however, have become increasingly blurred. We've seen it with armed conflicts and geopolitical events in recent times, such as the Russo-Ukrainian war and the Israel-Hamas conflict, where cyber criminal organisations and hacktivist groups are employed as proxies for nation states enforcing their foreign policy.

Getting into the Mind of the Adversary

Behind every cyber attack there is a human with a motive. As with any crime, the criminal will always have a motive. This motive will differ depending on the crime and perpetrator. A burglar wouldn't be breaking into a house for the same reason a murderer would for instance. Naturally there is overlap in the motivation, capability, and intent of criminals, and this extends to the digital realms.

What we see nowadays is that large cyber criminal organisations operate like corporations. Their organisational structure, culture, and business models are similar to the corporate world. Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) operators such as Conti employs technical staff to act as 'technical support' for their victims, taking them through the ransom payment and decryption processes of the operation. To the malware engineer or tech support agent working in these organisations it's a means to an end. They work 9-5 and receive a monthly salary; those working in the 'sales' department even earn commission for every new affiliate they bring on. TrendMicro detailed the inner workings of different sized cyber criminal organisations in their report, "Inside the Halls of a Cybercrime Business". These organisations are mostly headquartered in Russia, where the Kremlin's stance on cyber crime is quite vague and the corresponding laws even more so.

Now are these criminal organisations just a case of Hanlon's Razor, or is there a level of awareness in all employees across every level of the business that what they are doing is immoral and highly illegal? Perhaps we could break it down to "big fish; little fish": to the low level employees working in the call centres and 'sales departments', this awareness is negligible. To them it's a 9-5 office job which puts food on the table, and chances are they won't be prosecuted for their crimes because it's not as frowned upon. The big fish on the other hand, they seem to operate with more malice. When we start to see these criminals as humans sitting in an office, typing away on a keyboard, the eerie image of a hooded cyborg sitting in a doomsday bunker somewhere in Siberia quickly fades away.

At its root, the question of "Why?" yields the same answer as "What drives someone to commit crime?" But that's enough criminology for one article.

The Attribution Challenge - Pinpointing the "Who"

In the world of CTI, everyone is competing for attribution. When a new intrusion campaign takes the digital world by storm, the gates open and the race begins to be the first to pin point the TA responsible. Attribution is a pain point for many CTI analysts and often brushed aside due to its resource- and time consuming nature.

Nevertheless, let's dive into some models and frameworks used to answer the question: "Who is responsible for this activity?"

The Pyramid of Pain

The Pyramid of Pain is tool used CTI to demonstrate the difficulty of attributing Indicators of Compromise (IOC) to an adversary. The goal of the pyramid is to increase an adversary's cost of operations.

The Pyramid of Pain (Source: David J. Bianco)

Threat actors (TA) always leave breadcrumbs behind, and as the Pyramid of Pain demonstrates, the more attributable those IOCs are, the tougher they are to identify. Finding the hash value of a malicious payload dropped onto a compromised computer is all too easy, but pin pointing the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to a specific TA is a much more challenging task.

In most incidents, the client mainly cares about containing the incident and preventing the same thing from happening in future. Thus, the most important IOCs at the time will be on the lower end of the pyramid. Quick fixes to prevent further spread or damage. Although this is not bad practice per se, it does leave one questions unanswered: "Who did this?"

The Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis

Enter the Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis, a model designed to form relationships between the 4-core features of a cyber intrusion:

Adversary: the threat actor/intruder/attacker

Capability: the adversary's tools and/or TTPs

Infrastructure: physical and/or logical resources used by adversary

Victim: the organisation or information system targeted and/or hit by adversary

The Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis (source)

Whilst attribution of cyber activity to a threat actor is a complex and tiresome process, the Diamond model has proven to be an excellent tool in this regard through both its core- and meta features. The goal of the model is to attribute behaviour to a threat actor not solely based on the analysis of the threat actor's TTPs. The Diamond Model's CTI value lies in identifying relationships between events, and in analysing events to understand adversarial behaviour. The model isn't meant to be used to look at an event as a point in time, but rather to track adversary activity over time.

The original Diamond Model paper details 7 axioms about intrusion events, victims, and adversaries which should be kept in mind when investigating and analysing adversary behaviour:

“For every intrusion event there exists an adversary taking a step towards an intended goal by using a capability over infrastructure against a victim to produce a result.”

“There exists a set of adversaries (insiders, outsiders, individuals, groups, and organizations) which seek to compromise computer systems or networks to further their intent and satisfy their needs.”

“Every system, and by extension every victim asset, has vulnerabilities and exposures.”

“Every malicious activity contains two or more phases which must be success- fully executed in succession to achieve the desired result.”

“Every intrusion event requires one or more external resources to be satisfied prior to success.”

“A relationship always exists between the Adversary and their Victim(s) even if distant, fleeting, or indirect.”

“There exists a sub-set of the set of adversaries which have the motivation, resources, and capabilities to sustain malicious effects for a significant length of time against one or more victims while resisting mitigation efforts. Adversary-Victim relationships in this sub-set are called persistent adversary relationships.”

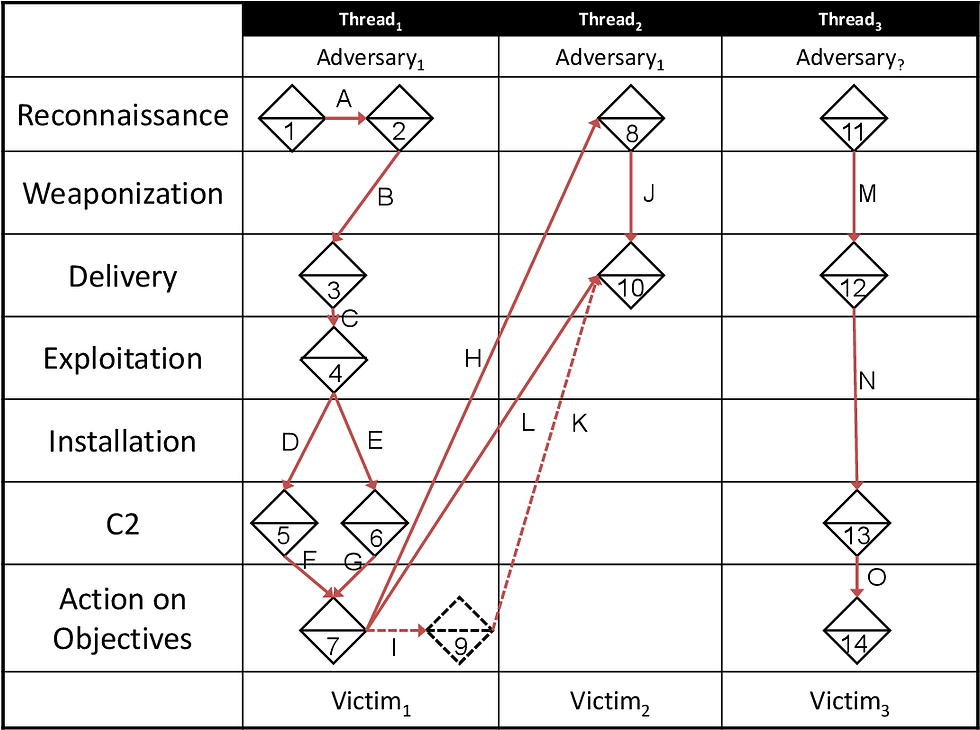

Another notable intrusion analysis model is the Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain, which provides a linear framework for adversary progression throughout a cyber attack. When incorporated with the Diamond Model, one can create an activity thread which illustrates axiom 4 that "an adversary does not operate in a single event against a victim, but rather in a chain of causal events within a set of ordered phases in which, generally, each phase must be executed successfully to achieve their intent."

An example of an activity thread combining the Cyber Kill Chain with the Diamond Model (source: Fig. 6, Diamond Model original paper)

Taking it one step further, one can create an activity-attack graph, which aims to go beyond historical intelligence and anticipates future paths an adversary may take using analytical tools such as Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH).

An example of an activity-attack graph (source: Fig. 8, Diamond Model original paper)

An activity group refers to a collection of events and activity threads that share common characteristics or procedures. Creating such a group provides a deeper pool of data for analysis. This information can be leveraged to automatically connect events and devise strategies for addressing them. Additionally, it enables the identification of adversaries by recognising patterns in their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and infrastructure usage across different events and threads. Once adversaries are identified, further insights into their TTPs can be gained, aiding in the development of effective mitigation strategies.

The Diamond Model paper gives us the the following steps for creating and analysing activity groups:

Analytic problem: define the question you’re trying to answer (e.g., “Who is the adversary we're dealing with?")

Feature selection: define the event features and adversary processes you’ll use for classification and clustering

Creation: create activity groups from events and activity threads

Growth: integrate new events into activity groups

Analysis: analyse activity groups to answer analytic problem from step 1

Redefinition: redefined activity groups as needed, as adversaries change

When an incident occurs, or an organisation becomes the victim of a cyber attack, the focus is primarily on plugging the leak before they take on more water. However, through the use of analytical tradecraft and intrusion analysis models, CTI analysts can analyse adversarial behaviour and attribute the activity to a threat actor. This can prove valuable in anticipating and preventing future risk of intrusion. Getting into the mind of the adversary and identifying the driving forces behind their activity allows one to gain the upper hand when defending against seemingly invisible threat actors.

I'll end off with the following quote from Sun Tzu's Art of War:

"If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle."